A framework for going from “who broke dev?” to confident, isolated, progressive delivery

The Problem We’re Really Solving

You have multiple product teams, each owning a slice of a larger integrated platform. Everything runs in Kubernetes. You have a control plane team managing shared services. And you have a dev environment that has become a graveyard of broken integrations, finger-pointing, and blocked engineers.

The root cause is simple: dev is being used as a scratch pad, but it’s expected to behave like an integration environment. These are fundamentally incompatible goals.

The strategy laid out here solves this by giving each stage of validation a clear purpose, clear ownership, and clear entry/exit criteria — enforced via GitOps so that environment state is always driven from Git, not from someone’s terminal.

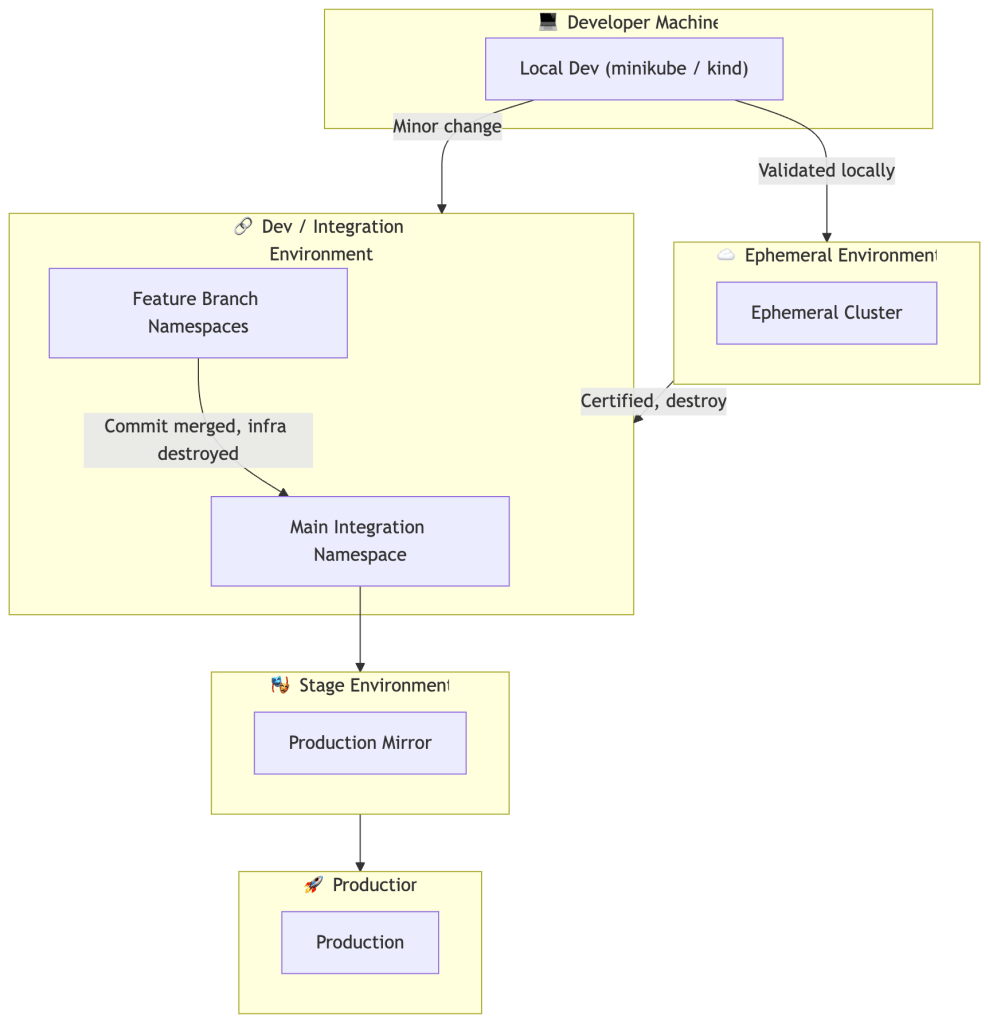

The Proposed Environment Topology

Before diving in, let’s be explicit about the landscape:

- Control Plane: shared services (platform, security, observability, identity, etc.)

- Dataplanes: mostly product-dedicated, occasionally shared between 2-3 products

- Teams: multiple product teams + a control plane team

- Environments: dev, stage, prod — plus two new constructs: local and ephemeral

The Five Layers Explained

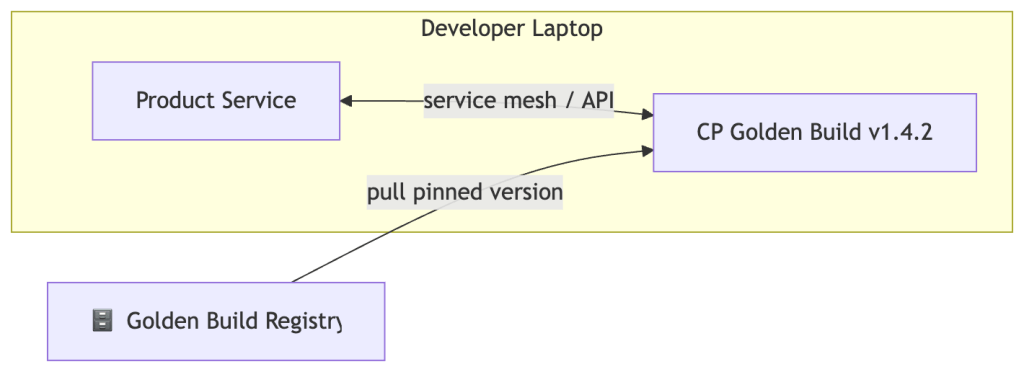

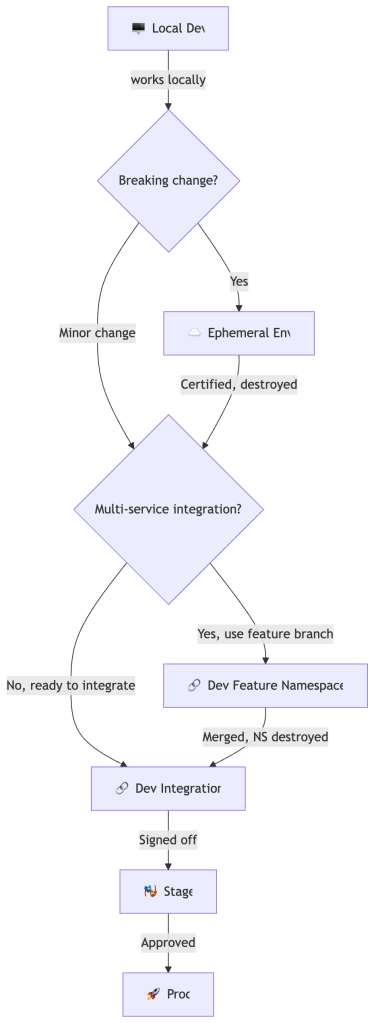

Layer 1: Local Development

Every product team owns a reproducible local stack. This means:

- A minimal control plane golden build (versioned, published by the CP team)

- The team’s own product, running locally via minikube or kind

- Ideally a

make dev-upor Tilt/Skaffold workflow that brings everything up in minutes

The key discipline here: the control plane golden build is not “whatever I last pulled” — it’s a versioned artifact. This prevents the silent version drift that causes “works on my machine” bugs before the code even reaches dev.

In practice, this golden build is delivered as a versioned Helm umbrella chart or Kustomize base that packages the minimal platform components required for local integration — typically a local ingress controller, a service mesh (or a lightweight stub), an identity provider mock, and OTEL collector sidecars. The goal is not to ship a replica of production, but a representative enough slice that integration bugs surface locally before they reach shared infrastructure.

What this catches: the vast majority of development bugs — logic errors, API contract violations, configuration mistakes — without ever touching shared infrastructure.

Critical gap in most teams: local environments are often not maintained or are underpowered. The control plane team needs to treat the minimal golden build as a first-class deliverable. If it’s a pain to run locally, engineers will skip this layer and go straight to dev, which is exactly how dev gets broken.

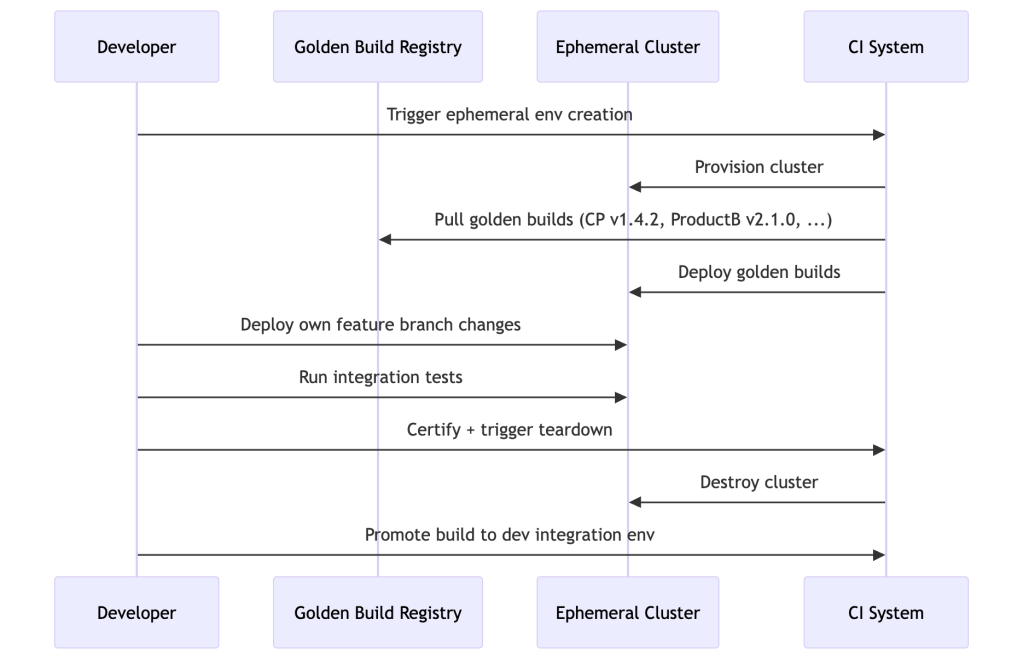

Layer 2: Ephemeral Environments (On-Demand, Time-Boxed)

This is the most powerful and underused pattern. When a developer is making a backward-incompatible change — a breaking API contract, a schema migration, a security policy change that affects other products — they need a full integration environment that they fully control.

The model:

- Spin up a dedicated environment (namespace or cluster — see isolation trade-offs below)

- Deploy your changes

- Pull golden builds of every other product/service you need to integrate with — the versions you don’t own and didn’t change

- Test, certify, and destroy

Namespace vs. Cluster Isolation

This is a decision point that matters significantly, and the wrong choice in either direction is costly:

| Isolation Level | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Namespace | Fast provisioning, cheap, reuses cluster infra | Weak isolation, shared control plane, shared CRD registry |

| Cluster | Strong isolation, independent control plane | Slower to provision, significantly higher cost |

Namespace-based ephemeral is appropriate for most feature integration scenarios: stateless services, minor API changes, new endpoints. Cluster-based ephemeral is required when changes involve CRD modifications, service mesh upgrades, network policy changes, or control plane component experiments. Applying a CRD change in a namespace-based ephemeral environment will affect every other tenant in the shared cluster — that’s a cluster-scoped operation.

Why “optional” is the right call: not every change needs this. A UI copy change or a single-service bugfix doesn’t justify spinning up a cluster. The trigger for ephemeral is backward incompatibility or cross-team API contract changes — this should ideally be detectable via API schema diffs in CI and surface a recommendation to the developer.

Cost governance is non-negotiable: ephemeral environments need automatic expiry (e.g., 48-hour TTL with optional extension) and cost attribution per team. Without this, they get forgotten and accumulate cloud spend. Implement hard TTLs and surface spend dashboards per team — treat it the same as any other shared resource quota.

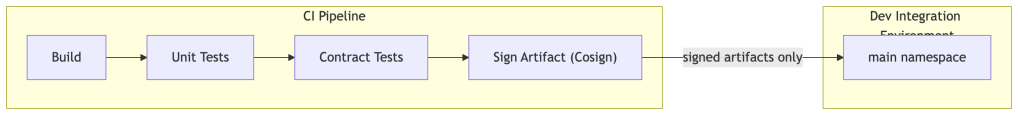

Layer 3: Dev as an Integration Environment

Dev stops being a playground. The rule is simple: only signed-off, CI-validated builds get deployed to dev. This single constraint changes the entire culture around the environment.

“Signed” here is not conceptual — it means OCI artifact signing via a tool like Sigstore Cosign, integrated into CI, producing a verifiable signature that the artifact has passed all required gates. The GitOps controller (Argo CD or Flux) only reconciles images that carry a valid signature. Unsigned images are rejected at deployment time, not discovered after the fact.

The control plane team owns the deployment schedule for dev — defining when the integration environment is refreshed and which golden builds are “current.” Product teams promote their signed builds via a PR to the environment repository; the GitOps controller picks up the change and reconciles. This keeps Git as the single source of truth for what is deployed where.

Observability is not optional here. Dev needs structured, correlatable telemetry — distributed traces, structured logs, and metrics — to diagnose integration failures. Specifically: correlation IDs must propagate across service boundaries, a minimal OTEL collector must be wired up and auto-configured, and trace data must be queryable without needing to SSH into a pod. A broken integration in dev without traces is just guessing with extra steps.

Layer 4: Feature Branch Environments (Lightweight Isolation within Dev)

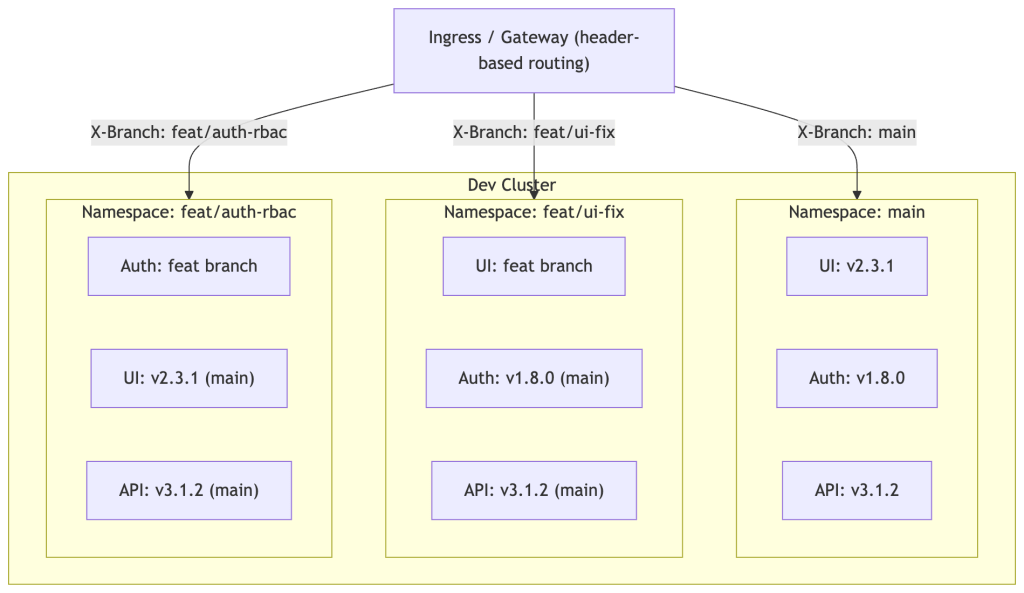

This is the most operationally nuanced piece. For minor, non-breaking changes, developers need a way to test integration without either (a) polluting the main dev namespace or (b) the overhead of a full ephemeral cluster.

The solution: namespace-per-feature-branch within the dev cluster, with traffic isolation.

How it works in practice:

- Feature branch push triggers namespace creation in dev

- Only the services the developer owns and changed are deployed from the feature branch; everything else is proxied to the main namespace or deployed from main’s golden builds

- Traffic routing is header-based (e.g.,

X-Feature-Branch: feat/ui-fix) or via virtual services in a service mesh - Merge to main → CI job deletes the feature namespace automatically

Hard problems that need explicit design decisions:

1. Header-based routing only works for HTTP. This is an important constraint. Header injection works well for synchronous HTTP/gRPC services where you control the client. It does not work for Kafka consumers, CronJobs, background workers, or any async workload. For event-driven services, you need topic-per-feature-branch or a separate consumer group strategy. Define the isolation model per workload type, not one-size-fits-all.

2. Shared stateful services. Feature namespaces cannot share a database with main without risking data corruption. Schema-per-feature (Postgres) is a common approach, but it only provides partial isolation — PostgreSQL extensions, global roles, and large migrations are cluster-scoped and can still cause cross-feature contamination. Schema isolation reduces risk; it does not eliminate it. For full isolation of stateful concerns, prefer mocking or a dedicated lightweight database instance per namespace.

3. Service discovery across namespaces. When a feature-branch UI calls Auth, should it call the feature-branch Auth (if one exists) or fall back to main? This fallback routing logic needs to be explicitly defined — naive approaches cause subtle cross-namespace contamination that is extremely hard to debug.

4. CRD versioning. This is the subtlest and most disruptive problem in multi-team Kubernetes. CRDs are cluster-scoped resources. If the control plane team upgrades a CRD while feature namespaces are running against an older version of that CRD, those namespaces can break silently or catastrophically. Any CRD change must be backward-compatible, and the upgrade must be coordinated across all active feature namespaces. This is one of the strongest arguments for preferring cluster-based ephemeral environments for control plane changes.

5. Certificate and identity propagation. mTLS and service identity in a service mesh get complicated when services span namespaces. The control plane team needs to provide an explicit model for how SPIFFE identities are scoped and how cross-namespace trust is granted.

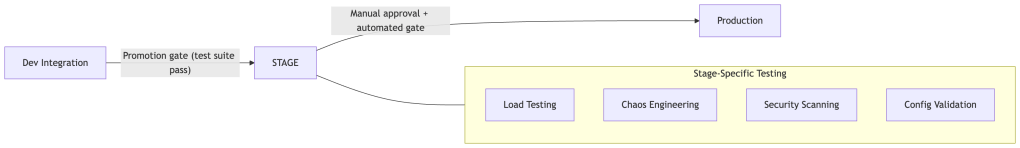

Layer 5: Stage and Production

Stage should mirror production topology and configuration semantics, even if scaled proportionally. In practice, full resource parity is rarely achievable — teams typically run stage at 30-50% of production capacity. That’s acceptable as long as the topology (same number of service replicas relative to each other, same network policy structure, same service mesh configuration) is preserved. What kills you is configuration divergence, not resource size.

This is also where load testing, chaos engineering, and security scanning should live — not in dev, where you can’t trust the build quality, and not in prod, where the blast radius is real.

A Concrete Scenario End-to-End

Abstract patterns are useful; a concrete walk-through is more useful. Here’s what this model looks like when it works:

Scenario: Team A owns the Auth service and is changing the token response shape — a backward-incompatible API change that affects the UI team (Team B) and the API gateway (owned by the control plane team).

- CI detects the breaking change via API schema diff on pull request open. It flags the change as requiring ephemeral validation and blocks promotion to dev.

- Team A provisions a cluster-based ephemeral environment (cluster-based because they’re modifying a CRD used by the auth operator).

- They pull golden builds of the UI (v2.3.1) and the API gateway (v1.8.0) from the registry. They deploy their Auth feature branch alongside these.

- Integration tests run. They discover the UI breaks on the new token shape — caught here, not in dev.

- Team A coordinates with Team B. Team B cuts a feature branch (

feat/ui-auth-token-compat) and adds it to the ephemeral env alongside the Auth change. - Both changes validate together. Tests pass. Team A certifies the environment and triggers teardown.

- Both teams promote their signed builds. The GitOps controller reconciles dev. Dev integration tests pass.

- Normal promotion to stage and prod follows.

Total blast radius: one ephemeral cluster, two teams, zero disruption to dev.

Platform Team Ownership

A critical clarification: the control plane team’s role shifts significantly in this model. They are not just operating infrastructure — they are building an internal developer platform (IDP). That’s a product, and it needs to be staffed and resourced as one.

Platform team owns:

- Golden build registry and promotion governance

- Namespace provisioning automation (feature namespaces spun up/torn down via CI)

- GitOps controllers (Argo CD / Flux configuration and access control)

- Observability baseline (OTEL collector, trace backends, dashboards)

- Cluster lifecycle and CRD versioning strategy

- Resource quotas and TTL enforcement for ephemeral environments

Product teams own:

- Service code and build pipelines

- Consumer-driven contract tests against services they depend on

- Feature namespace usage and cleanup

- Promotion decisions for their own builds

Without this explicit ownership split, the platform collapses into the classic “ops does everything, product teams do whatever they want” failure mode.

The Full Progression

Anti-Patterns to Avoid

These are the failure modes this model is designed to prevent. If you see them happening, the process is being bypassed:

- Dev as shared scratch pad. The moment someone manually deploys an unsigned build to dev, the integration baseline is contaminated. Enforce signing at the GitOps controller layer, not on trust.

- Feature namespaces without quotas or TTLs. They will accumulate. Set hard limits and automate cleanup.

- Ephemeral environments without TTLs. Same problem, higher cost per unit. Always set a maximum lifetime with an explicit extension process.

- Golden builds without a promotion owner. If “golden” means “latest passing CI build,” it’s not golden — it’s just another label on an untested artifact. Someone must own and approve promotion.

- Manual deploys to dev or stage. If it bypasses GitOps, it bypasses the audit trail, the signature check, and the environment state guarantee. Block it at the RBAC layer.

- Shared stateful services across feature namespaces. This will cause non-deterministic test failures that are nearly impossible to attribute. Always isolate state per namespace.

- CRD upgrades without coordination. A CRD upgrade in a shared cluster is a breaking change for every active feature namespace. Treat it as such.

What’s Still Missing

Even with all of the above, a few gaps remain worth addressing explicitly:

Rollback and incident response path. The flow described is a forward-delivery path. The reverse — rollback from prod, and the incident investigation path (which environment do I use to reproduce this?) — needs a separate, equally explicit playbook. Engineers under pressure will do the wrong thing (reproduce a prod incident in stage, contaminating it) if there’s no clear procedure.

Environment parity and configuration management. Dev, stage, and prod will drift in configuration over time. A deliberate secrets and config management strategy — external secrets operator, Vault, or environment-specific Kustomize overlays — needs to be in place from day one. Config differences between environments are a leading cause of “works in dev, breaks in stage.”

Contract testing as a first-class gate. Consumer-driven contract tests (e.g., Pact) between teams, run in CI on every pull request, catch breaking changes before they reach any environment. This complements the ephemeral environment — contract tests validate at test time; the ephemeral environment validates at runtime. Both are necessary.

Summary

| Layer | Purpose | Entry Criteria | Exit Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local | Develop & unit validate | Always | Builds and passes local tests |

| Ephemeral | Validate breaking/cross-team changes | Breaking change or CRD modification detected | Integration tests pass; cert issued; destroy |

| Dev Feature NS | Lightweight multi-service branch testing | Minor change, needs HTTP integration testing | Merged to main; NS auto-destroyed |

| Dev Integration | Continuous integration baseline | Signed artifact (Cosign), contract tests pass | All integration tests green |

| Stage | Production validation | Dev integration green | Load tests pass; manual sign-off |

| Prod | Serve users | Stage approved | N/A |

The core philosophy: every environment has one job. The moment an environment is asked to do two jobs simultaneously — scratch pad and integration baseline — it fails at both.

Done right, this moves your engineering culture from “who broke dev?” to “I certified this before it got to dev.” The hardest part isn’t the tooling — it’s the discipline. Tooling can enforce gates, but teams need to genuinely treat each layer as what it is, not as a convenient shortcut to the next one.

This architecture is most effective when the platform team treats their output as a product — not as infrastructure support. The golden build registry, the namespace provisioning automation, the GitOps controllers, the observability baseline: these are features, with roadmaps, with SLOs, and with users.

Leave a comment